Following on from the Centre for the New Midlands’ recent webinar, which explored the case for community led housing (CLH) and the role it could play in enhancing the housing mix across the West Midlands, Abigail Ryan (Development Manager, West Midlands Urban Community Homes) provides her thoughts on the role that local and regional policy makers can play in enabling community led housing.

“We have a rich heritage of CLH in the West Midlands, with thousands of community led homes managed by co-operatives, tenant management organisations, self-help housing groups and community associations. The right policy environment can help to bring forward the existing pipeline of 1,097 homes[1] and inspire the development of new ones.

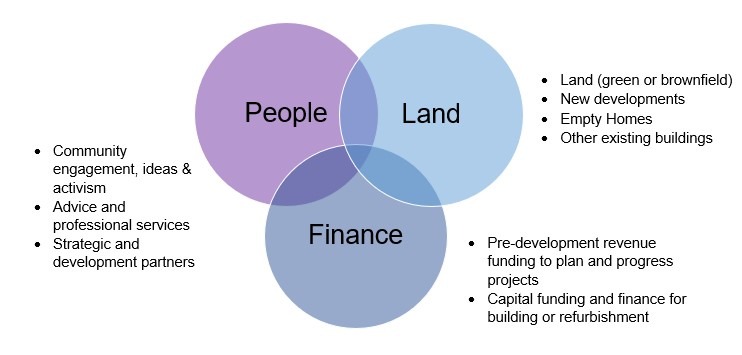

At the webinar, I spoke about three key ingredients needed to make CLH happen:

Strategic support

Leadership and championing CLH at a political and officer level can help to unlock all of the ingredients above by creating a supportive policy environment across housing, planning, asset management, finance, neighbourhood and community development.

A great example is Birmingham City Council’s recently developed CLH policy. This sets out how BCC will work together with wMUCH (more about us at the end) to promote, enable and support CLH. It formalises their commitment to provide opportunities for communities to have greater influence and involvement in how their areas are run, in the context of meeting housing supply targets. CLH is an additional mechanism to provide more social and affordable housing in different ways.[2]

Facilitating partnerships between communities and developers

This is another strategy that can unlock all of the ingredients above. Development and management partners could be Housing Associations, local authority house builders, ALMOs, or private developers; working to meet social and affordable housing priorities in your area. With the right skills and motivation, they can act as a vehicle for CLH by adopting new models of community management and stewardship. This can start in different ways – with an existing CLH group or organisation; or initiated by a developer who facilitates community group development and builds community stewardship into their scheme. The activities to recruit, train and support founder members of a CLH group are often carried out by a specialist CLH support organisation and wMUCH can help with this community building work – see contact details at the end.

For example, the Old Oak Housing Co-operative in Carmarthen came about when the County Council asked Gwalia Housing to develop a site for 27 family homes and initiate the development of a housing co-operative. Specialist CLH support organisations did extensive training and development work with founding members drawn from the Council’s waiting list and the tenants developed into a Co-op.

In Leeds, private developer CITU is developing the Climate Innovation District as part of the Aire Valley Corridor regeneration programme. They are working in partnership with Leeds Community Homes to develop community within the overall scheme, with the intention of establishing a CIC to own the freehold of 16 pepperpotted affordable rented and discounted equity flats across the development.

Unlocking access to land

Despite challenges around land supply, urban policy makers around the country have found creative ways to do this. For example, by identifying sites that are too small, have complex conditions or do not fit mainstream approaches to development; as seen through the GLA’s Small Sites Scheme in London. In Brighton, Bunker Housing Co-operative are building homes on small local authority infill sites on existing council estates, on a long lease from the council. The use of long leases to CLH organisations also provide councils with a long term income stream to build their asset base.

Procurement frameworks and land disposal templates can also enable CLH through disposals of assets. Occasionally discounted value sites have been made available. It is also possible to define best value to incorporate the social and environmental impact CLH can create, beyond capital receipts and the homes themselves. Sometimes this is unlikely due to budgetary constraints. But even so, designated sites, exclusivity periods on sales or deferred payment schemes can enable community organisations to raise the finance they need to purchase sites at a market rate. Bristol City Council is making sites available to test and deliver innovative and affordable housing solutions over the five years as part of the city’s Housing Festival.

Simply providing data on available land and existing empty buildings owned by the council or other public bodies can make a huge difference, as this is often difficult for groups with limited resources to navigate.

Empty homes

Refurbishment of empty homes to bring them back into use can be a great way for CLH groups to get started, while tackling neighbourhood decline. Examples such as Giroscope in Hull and Canopy in Leeds demonstrate the potential success of this approach. In Hull, Giroscope transformed whole areas of empty properties, with support from the Council through the Hull Partnership Empty Homes Programme. In Leeds, the Council has transferred empty properties, offered long leases and provided additional finance to Canopy. Policy makers can develop an Empty Homes Strategy, utilise CPO powers and land disposal mechanisms to help achieve this.

Planning

Planning authorities can utilise statutory planning policies and frameworks like local and neighbourhood plans, masterplans, local development orders and design codes to allocate land and give a measure of priority to CLH. Planning gain mechanisms such as section 106 and commuted sums can enable further. Bradwell CLT in the Peak District acquired twelve new build houses from a private development to be given to them at no cost as the S106 contributions from the developer, by writing these requirements into the Neighbourhood Plan. Similar principles could apply in the masterplanning of regeneration schemes and the development of new settlements.

Existing stock

Supporting an increase in community control and stewardship in existing Council and Registered Provider stock is another way to help support vibrant neighbourhoods and community wealth building. Take Bushbury Hill Estate Management Board, who manage a large estate in Wolverhampton. They’ve now partnered with the Council and its ALMO to develop new homes on a vacant site and a number of infill sites.

Custom and self-build

Local authorities can support CLH whilst fufilling their legal duty to promote self-build, by selling to groups of community self-builders on the register. Like the case of Petersfield CLT, formed as a vehicle to facilitate the development of a self-build site allocated as such in the Neighbourhood Plan.

Funding and finance

Both government and independent funding at the national level has played a critical role in the growth of the CLH sector in recent years and new research setting out CLH’s high value for money[3] is boosting the case for renewal of these kinds of funds.

We’ve also seen innovative approaches to funding and finance at the local and regional level around the country. Local authorities have used pots such as commuted section 106 sums, second homes Council Tax, New Homes Bonus or retained RTB receipts; to provide both grant funding and capital for revolving loan funds. Others have utilised Public Works Loan Board lending to invest in schemes alongside other public, commercial and social lenders. Examples include Leeds City Council financing Chapeltown Cohousing and Hull City Council investing in the Goodwin Development Trust.

So, what next? An invitation

West Midlands Urban Community Homes is a new hub set up to provide knowledge and expertise to inspire and support a new wave of community led housing in the West Midlands. We do this by working with a wide range of stakeholders to help unlock the people, land, finance and development skills needed to enable community led housing. If you’d like to hear more about work going on in your area and explore how we could help you to develop and implement some of these ideas, please get in touch at abigail.ryan@wmuch.org.uk”

[1] Housing by the community, for the community: An assessment of the value for money of community led housing in England, Capital Economics, 2020

[2] See ‘The Case for Supporting community-led housing’ in Community Led Housing: A key role for local authorities, CCIN

[3] The research was commissioned by the National CLT Network, funded by the Nationwide Foundation and Power to Change and conducted independently by Capital Economics.

About Abigail Ryan:

Abigail has recently joined West Midlands Urban Community Homes and is currently working to establish wMUCH as a new hub for knowledge and expertise that exists to inspire and support a new wave of community led housing in the West Midlands. wMUCH will do this by connecting new community groups, established community organisations, housing associations, developers and local authorities to the support and guidance they need to deliver successful projects, including their expert advisors. They will also work collaboratively with a wide range of stakeholders to help unlock the land and finance needed to enable community led housing.

Abigail has a varied professional background across the not for profit sector; from programme and business development in charities, to grant making, social investment and consultancy. She is passionate about the power of communities to create a more equitable land and housing system.

Connect with Abigail on LinkedIn