Professor Bob Stone is a Human Factors specialist and a 34-year “veteran” of the international Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality community.

In this article, Professor Stone warns that as we are about to enter the fourth XR (eXtended Reality) hype cycle, the West Midlands is perfectly placed to thrive in this space – IF it learns the lessons of the past 30 years and mobilises its significant expertise to deliver social impact and something truly unique.

Examples of “XR” or “eXtended Reality” – somewhat of a marketing term encompassing Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality (VR, AR and MR)[1] – are, today, ever-present when browsing online, reading newspapers and trade press, or watching reality and fictional TV programmes. And they are almost always accompanied by images of headset-wearing users, interacting with all manner of real and imaginary 3D worlds. During the COVID-19 pandemic, multiple examples of virtual meeting sites have become evident, and conferences, parties, even educational sessions have been witnessed, often populated by strange, disembodied avatars performing all manner of frenetic movements and gestures. For many, XR is still looked upon as an “advanced” form of gaming, delivering scifi combat zones to living rooms, or encouraging youngsters to search all corners of the planet for diminutive cartoon characters. But it’s much, much more than that. It always was, as I discovered in 1987 in NASA’s California research labs, where headset-bedecked users were being trained to supervise space-walking astronauts, or to control space station maintenance robots.

One of my career highlights was leading a small team of scientists and industrialists, based at the UK’s National Advanced Robotics Research Centre in Salford, Greater Manchester. In 1993, we launched the world’s first collaborative VR initiative, fully funded by industry. Over three years, VRS (Virtual Reality & Simulation) offered a tiered membership to large and small companies, and to those keen to maintain a “technology watch”. We conducted a range of “concept capability” projects, delivering results to the sponsors’ doorsteps, allowing their employees to gain first-hand experience and to provide feedback – good and bad – about VR’s future potential. Indeed, the VRS programme generated results that helped many companies in defence, nuclear, oil and gas, retail, nuclear power and healthcare build and sustain their adoption of VR for many years, some even to the present day.

But, as the 21st century approached, and despite the launch by what was then the Department of Trade & Industry of the “UK Virtual Reality Forum”, the future for the community was looking very bleak indeed. In an article for the Times Higher Education Supplement in July, 2005, I wrote:

“By the end of the 20th Century, VR would [it was claimed] help us to abandon the keyboard, mouse, joystick and computer monitor in favour of interfaces exploiting the skills we were born with. We would all interact naturally with virtual objects and people whilst “immersed” within a multi-sensory, 3D computer-generated world.

As we now know, this brave new world simply did not happen. Despite sizeable early investment, national initiatives, expensive (and unexploited) European projects and the widespread launch of centres of academic excellence, VR delivered very little of use to the global IT community. A handful of organisations actually adopted VR, but most were simply scared off by its complexity and cost. The VR supply companies have either passed away or are hanging on by a thread and academic centres have closed or are fast becoming expensive technology museums …

… Lessons must be learned. Academic centres … are not the answer; neither is massive early investment in large consortia. Technology of this nature has to be designed in conjunction with the end user, packaged in a form the end user can understand and taken out to the end user for immediate use; this is where the VR centre of yesteryear failed. In the very early days of VR, innovation and end user focus came from small entrepreneurial companies, many of whom were later ignored as the academic community set out on its path of technological domination … had early R&D projects taken account of the innovative talents of these companies, then VR would be far more advanced today than is the case.”

There was one light on the horizon, and one in which West Midlands organisations played a small part – the so-called “serious gaming” community. Serious gaming exploited computer games software tools such as those used to produce the “first person shooter” or “role-playing” games still being enjoyed today by youngsters and adults alike. These tools took the form of software development kits and other digital content, regularly released by leading games developers shortly after the publication of a new product (FarCry, Half-Life 2 and Unreal were good examples), many of them free of charge. The availability and affordability of these tools rapidly generated interest from the “serious applications” community, including those responsible for designing training and real-time visualisation systems for defence, surgery, heritage and education, to mention but four examples.

Indeed, if it wasn’t for the gaming community which, in my opinion single-handedly turned the tide of fortune for VR, we would not today be taking advantage of a range of accessible, affordable and highly usable software and toolkits, not to mention online assets which are capable of significantly minimising the time from concept to delivery. But even then, at the turn of the century, this new-found catalyst had its problems, not unlike the VR situation a few years prior. Problems such as significant and poorly policed investments fuelled by ludicrous claims of growth and payback contained in over-priced works of marketing fiction. Other issues included ill-conceived national initiatives, even more failed or unexploited European projects, and the inevitable emergence of short-lived centres of “academic excellence”.

This trend is something we, who have survived the past three decades of VR, SG and XR, have witnessed time and time again, roughly every seven years; we are about to enter the fourth XR hype cycle. Already we are witnessing crazy investment levels, start-up examples with weak business and little future resilience and yet more academic centres forming. Money wasting due to reinventing the wheel are rife. Literally on a daily basis, I find myself losing the will to live when witnessing project examples online that have already been delivered in the past, sometimes more than once. And the truly frustrating thing about these reinventions of the wheel is that we can demonstrate their earlier development and exploitation using powerful examples from West Midlands organisations!

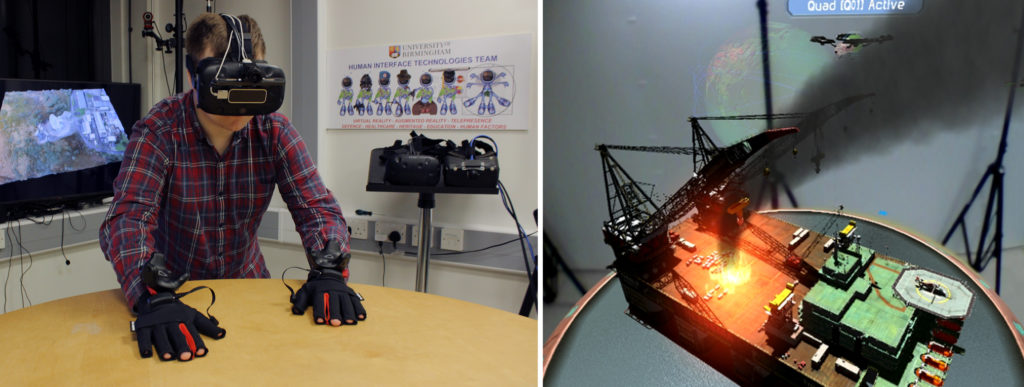

Not only has our region demonstrated leadership in the gaming sector for many years, we can justifiably boast many UK, and often world-leading achievements in the VR, AR and MR field as well. For example, a unique, world-leading Mixed Reality training solution for defence and civilian paramedic training (five years ahead of similar developments worldwide); identical claims can be made for innovative MR solutions for military command and control. Breakthroughs in exploiting VR for mental and physical wellbeing and rehabilitation in hospitals. The first in-depth study of using VR for future naval trainees, the results of which were adopted by the navies of Australia and Canada. One University being singled out as an exemplar for industrial collaboration in this field. An unrivalled STEM and public engagement track record. The delivery of a major VR demonstration celebrating the 400th anniversary of the Pilgrims’ journey to the New World. World-leading expertise in the crucial field of human-centred design, something so often ignored in the high-tech arena, but of crucial importance in ensuring that XR technologies delivered for real-world exploitation are actually fit for human use.

The 1990s may seem like a generation away, but the hard lessons learned during that decade are still being ignored today. It’s a fragile time throughout the commercial XR community. VR-based Location-Based Entertainment Centres face an uncertain future; not just, as in the 1990s, through the pressure of trying to refresh their “experiences” on a timely basis, but also because of the public’s renewed awareness of issues such as health and safety and hygiene – a major concern in the sharing of wearable technologies, of course. Small start-ups are attracting hitherto unheard of levels of investment, often underpinning their future growth predictions with content from the same expensive and unbelievable marketing reports that were misleading companies and investors in the past. And for what? For allegedly innovative developments that actually have very little chance of sustaining growth. All too often we hear stories of investments being extinguished prematurely during the over-marketing of ill-conceived products and services, or as a result of the company participating in too many of the conferences that exist on the international XR stage. And all too often this happens long before a resilient and believable business plan has been put in place and the spectre of cash flow appears over the horizon.

Perhaps, nearly 30 years on, it’s time for another VRS initiative, but this time bringing together all of the best that the West Midlands has to offer in pursuit of one or two truly innovative projects. That’s “innovative”, by the way … not replicating what has gone before simply by using the latest VR hardware (something we see all too often masquerading as innovation in online postings and newsletters). Perhaps it’s time to build on the globally impressive, yet under-publicised and under-marketed track record and achievements of the West Midlands in this field. Perhaps we need to tackle some genuinely societally high-impact applications – climate change, protection of nature, inclusive education, care of the elderly, and so on. Perhaps it’s time to hold academic institutions to account in this field, encouraging much, much more than boasting the biggest or most well-equipped VR centre. We need to ensure that genuine engagement occurs with industry and commerce, and that true research impact, not just more papers or presentations for the already-saturated international conference circuit, becomes the norm, rather than the exception. My brief article in the Times Higher Education Supplement is as relevant today as it was 16 years ago.

The breadth of skills in the region is extensive, from human factors to sharp-end experience of managing tech companies; from creative content design and programming to hardware design and integration. Today they exist as fragmented and fragile pockets of capability dotted around the region. Just imagine what they could do if they could be mobilised to produce something really unique and of sustainable social impact – something that would put the Midlands squarely on the digital map.

[1] For basic definitions, see https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/virtual-augmented-mixed-reality-basic-definitions-bob-stone/

About Professor Bob Stone, C.Psychol., FCIEHF

Bob Stone is a Human Factors specialist and the UK’s foremost immersive technologies specialist – a 34-year “veteran” of the international Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality community. In 1993, whilst researching VR and robotics at the UK’s National Advanced Robotics Centre, Bob established the world’s first industrial VR team, launching a countrywide collaborative VR initiative, wholly funded by industry.

Bob’s research has taken him from Royal Navy vessels conducting close-range weapons and missile trials to underwater operations onboard submarines and rescue submersibles; and from search-and-rescue helicopter missions to operating theatres and medical units throughout the UK, US and South Africa.

Today, as well as being an Emeritus Professor at the University of Birmingham, Bob works closely with the Royal Centre for Defence Medicine and various UK hospitals, researching the use of VR and MR for physical and mental health restoration and rehabilitation, and for the training of future military Medical Emergency Response Teams. He also has a passion for the Virtual Heritage arena, exploiting VR and AR to help make invisible rural and oceanic historic sites visible once again, particularly around the Plymouth area where he was born and bred.

In 2011, Bob was awarded the Ministry of Defence Chief Scientific Advisor’s Commendation for his contributions to Defence Science & Technology, and, more recently, his team received the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors 2020 Innovation Award for their defence medical work.

Connect with Bob on LinkedIn

Follow Bob on Twitter