As Her Majesty The Queen celebrates her 70th year on the throne, we are delighted to celebrate the achievements of our own ‘royalty’ – Professor Bob Stone, who looks back on his 35 years of working within the Virtual Reality sector.

In this article, Bob takes a look back at his journey and some of his key learnings throughout his illustrious career. Professor Stone – we salute you!

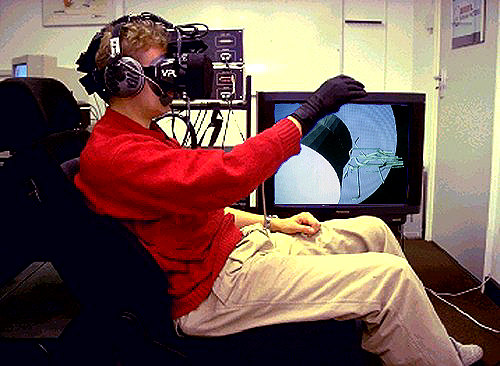

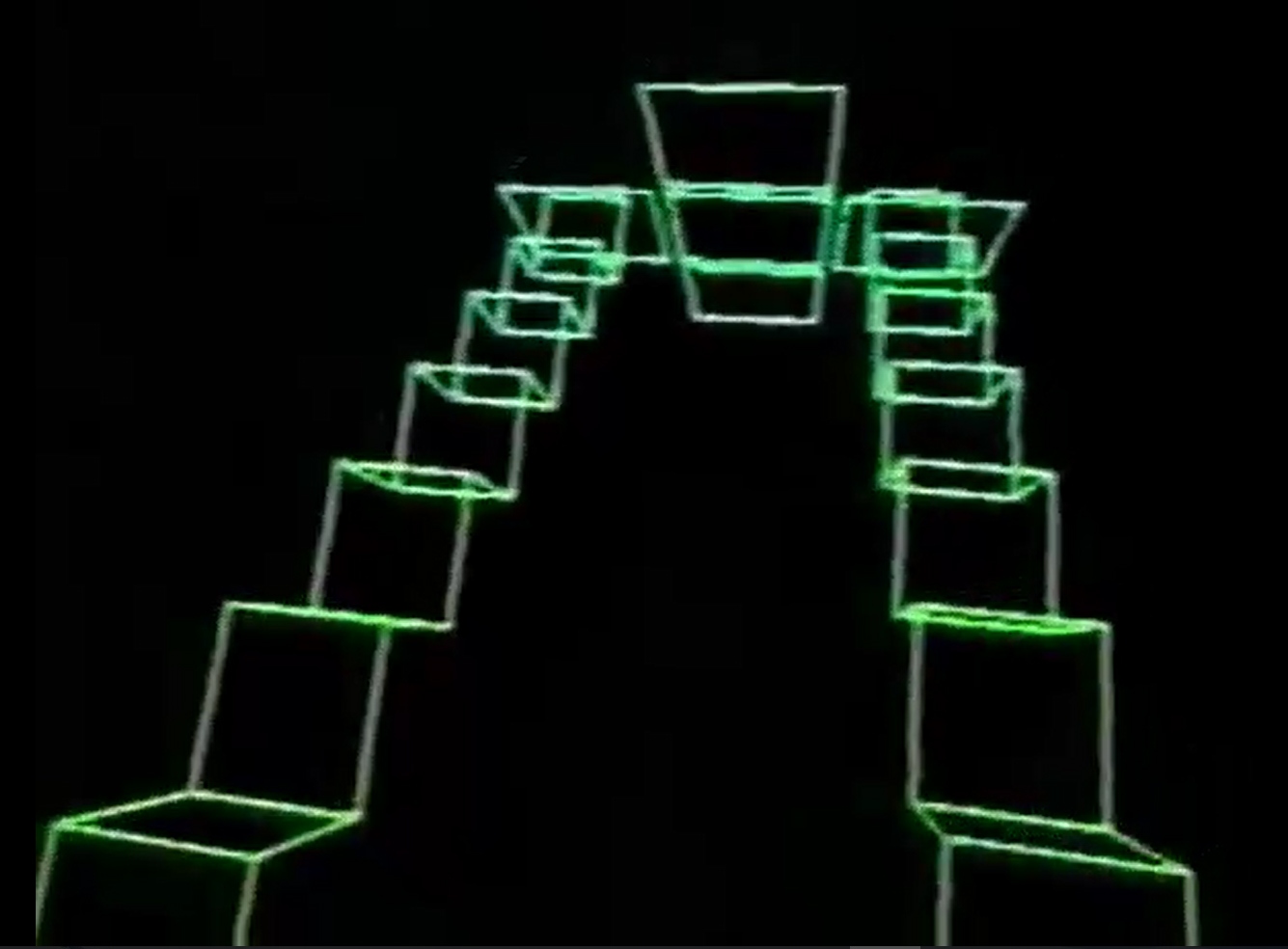

I consider myself very fortunate and proud to have been involved in the very early days of Virtual Reality, courtesy of a chance meeting with Dr Steve Ellis (of NASA Ames) at a Satellite Servicing Conference held in June, 1987 at the Goddard Spaceflight Center in Maryland. My British Aerospace Human Factors research team was, at that time, undertaking Low Earth Orbit telerobotics research projects for the European Space Agency and Steve persuaded me to “hop” over to San Francisco and Moffett Field to meet with the NASA Human Factors team. Whilst there, I was introduced to Dr Scott Fisher, who convinced me to don a prototype VR head-mounted display and early DataGlove, Scott’s demonstration meant that I was to become the first European to experience the revolutionary NASA VIEW (Virtual Environment Workstation) system. Ascending a simple, wire-frame 3D model of an escalator (when my vestibular system was convincing me I was standing still), was certainly a life-changing experience and one that has shaped my research and commercial career to this very day.

On returning to Britain, I set out on a journey to establish a UK Human Factors and industrial applications-focused VR programme and, six years later in July, 1993, courtesy of the results of my new role in the UK’s National Advanced Robotics Research Centre, that ambition was finally realised. The launch of the Virtual Reality & Simulation (VRS) Initiative in 1993 – a wholly industrially-funded project involving a range of companies, large and small – included BNFL, Rolls-Royce, the NHS, Sainsbury’s Vickers Shipbuilding (today BAE Systems) and many more. The 1990s were certainly a roller coaster ride of failures and successes, full of mixed emotions and often significant frustration at the lack of foresight and innovation on the part of the UK science and technology scene. Nevertheless, those years invoke many memories for me. Memories such as the 40 filming “takes” it took, in 1991, to get the telerobot sequence perfect for my short appearance on the first major TV documentary on VR, BBC Horizon’s Colonising Cyberspace (the robot’s fault, not mine!). Memories such as commissioning Division Ltd’s first transputer-based VR computer which enabled us to produce the first – very basic – example of Augmented Reality; and launching the world’s first Virtual Stonehenge model with the late, great Sir Patrick Moore at the London Planetarium; and presenting our research at the House of Lords, to an audience that included Edward Simons, Chairman of the Allied Entertainments Group and one of the Executive Producers of the film Lawnmower Man.

But my one big memory was, without doubt, inventing the world’s first haptic feedback glove, Teletact and working with the animatronics expert, the late Jim Hennequin, to bring a prototype into existence. And what an experience that was! We first exposed the fledgling VR community to Teletact at what became one of the most important early events in the international history of VR – a conference entitled Human-Machine Interfaces for Teleoperators and Virtual Environments. Held at the Sheraton Hotel in Santa Barbara (March, 1990), and co-chaired by Tom Sheridan and Nat Durlach (MIT), the conference drew together all of the “big” names to be in the world of VR – from VPL to Crystal River; from UNC to NASA; and from Exos to Fake Space Labs. Following that conference, Jaron Lanier’s VPL opened discussions with the Advanced Robotics Research Centre to investigate how the Teletact concept could be integrated with their DataGlove. But, by the time the unbelievably protracted negotiations had reached an early commercial stage, VPL’s fate had been sealed and their unfortunate demise was literally months away. The entertainment company Virtuality (then trading as W Industries) also took an interest in the Teletact technology, but the experience of dealing with them was not at all satisfactory. Discussions were held with the aim of entering into a partnership to integrate the pneumatic “airpocket” developments into their own Space Glove. Unfortunately, commercial discussions broke down, but W Industries went ahead and copied the Teletact concept, producing a prototype in time for a major launch at an early Imagina Conference in the South of France. Approaches by Robotics Centre personnel to W Industries and, later, Virtuality exhibition stands, were greeted by frenetic attempts by company representatives to remove the integrated gloves from view, locking them securely in protective cases! The Teletact experience was, sadly, short-lived. In October of 1990, the BBC’s science programme Tomorrow’s World ran a feature on the glove, featuring – as a tactile subject – Henry the Angora Rabbit! There was, at that time, a myth that any novel technology that appeared on Tomorrow’s World would experience an uncertain future. And so it was with Teletact. The pneumatic haptic concept was taken no further and the remains of the first prototype glove lay hidden in my garage until its “re-discovery” in August of 2014!

There was one other story associated with Teletact that, if things had been different, would have seen me becoming a millionaire in the early 1990s. But alas, as we were funded by the Government, we knew it was never to be. And I’m still not a millionaire! This story concerns the sudden and unannounced arrival at the Advanced Robotics Research Centre of three very interesting characters who had flown over to the UK especially to meet me. It so transpired that the party’s leader Larry was the CEO of what he claimed was the largest group of “adult emporiums” in the US and wanted to buy the intellectual property to Teletact with the aim of creating his own version of the “Excessive Machine”, as featured in the 1968 Jane Fonda science fiction film Barbarella or, the “Orgasmatron” in Woody Allen’s 1973 film Sleeper. At this point, it’s probably best to stop and leave the rest to the imagination!

Our major achievement in these early years, however, was, without doubt the launch of the VRS Initiative mentioned earlier. This came about following a chain of events following the publication of a short article in December 1992 by Elisabeth Geake, then the Technology Reporter of the UK’s New Scientist magazine. The article focused mainly on the launch, by Britain’s leading commercial VR development company Division, of the ProVision 100 VR system. During Elisabeth’s interview with me, I raised concerns about the lack of funding for VR research and development in the UK, especially as, in the main, companies had single-handedly helped to nurture the country’s European lead through investment of their own scarce funds. I also mentioned that, as a result of an invitation to give a Christmas Lecture to the UK Government’s Department of Trade & Industry (DTI), it was my intention to deliver a few “home truths” to national research funding bodies. As with many press features, these comments were well and truly taken on board and the article appeared in the 12 December edition (New Scientist, No.1851; p.18)…

“…Stone is meeting with the Science and Engineering Research Council and the Department of Trade and Industry later this month and will tell them: “You back us up so that we keep our lead””.

The BBC, having read the New Scientist article, decided to send a film crew to the Robotics Centre early in January 1993, with the aim of running a VR feature on the 9 O’Clock News. Another coincidence helped to make the feature a success. It just so happened that, at the time of filming, the Centre was in the process of evaluating one of the first new Silicon Graphics Crimson RealityEngines to enter the Country. The feature was not screened immediately after the filming session, due to the Gulf War and Operation Desert Storm. Nevertheless, the piece was finally transmitted on 19 January. The VR feature, presented by the BBC’s Science Correspondent James Wilkinson, lasted for a substantial (in BBC news terms!) 3½ minutes and included an immersive fly-through of a Trent 800 Aero Engine demonstrated by the Centre’s VR Team to Rolls-Royce 3 months prior, Silicon Graphics’ “Performer Town” demonstration hosted on the RealityEngine, a simulated nuclear fuel rod recovery, and some early molecular modelling research carried out by the University of York for Glaxo. The response to that one feature was incredible, with companies around the UK contacting the Centre to express surprise that real industrial applications of VR actually existed! Hence the launch of the VRS Initiative six months later.

I can’t stress enough how important the VRS Initiative turned out to be. Not only did it put the UK well and truly on the international map for real-world applications of VR, it generated a huge amount of experience – and hard knocks – of how to interact with industry and other potential adopters when trying to “sell” such a radically new technological concept. And, above all, it demonstrated how important it was to conduct projects following a strong human-centred design process. All in all, the VRS projects gave us a superb portfolio with which we could eventually split away from the Robotics Centre and to venture out into the “real” commercial world of VR. We launched VR Solutions Ltd in October 1995, just as the VR community was beginning to suffer its first and brutal period of “recession”.

One particular (and nearly disastrous) experience during the VRS days in this respect, was the development of the Minimally Invasive Surgery Trainer (MISTVR). Forgetting my Human Factors training, I fell into the trap – as is seen all too often, even today – of putting technology before addressing the training requirements of the end users. Using a £250,000 so-called “graphics supercomputer”, we demonstrated simulated deformable tissue, coupled with new hardware to deliver glasses-less (autostereoscopic) images to surgeons, and haptic feedback via a rather Heath-Robinson electromechanical contraption. The medical collaborators hated it and we almost had the contract cancelled. Fortunately, after four afternoons in the operating theatre with our surgical colleagues, following a human-centred design process, we saved the day and the much more affordable MISTVR was born, combining VR content with realistic (physical) medical instruments. In fact, MIST became the European de facto keyhole surgery trainer for over a decade, courtesy of the adoption of the technology by the prestigious European Surgical Institute (today the Johnson & Johnson Institute) in Hamburg.

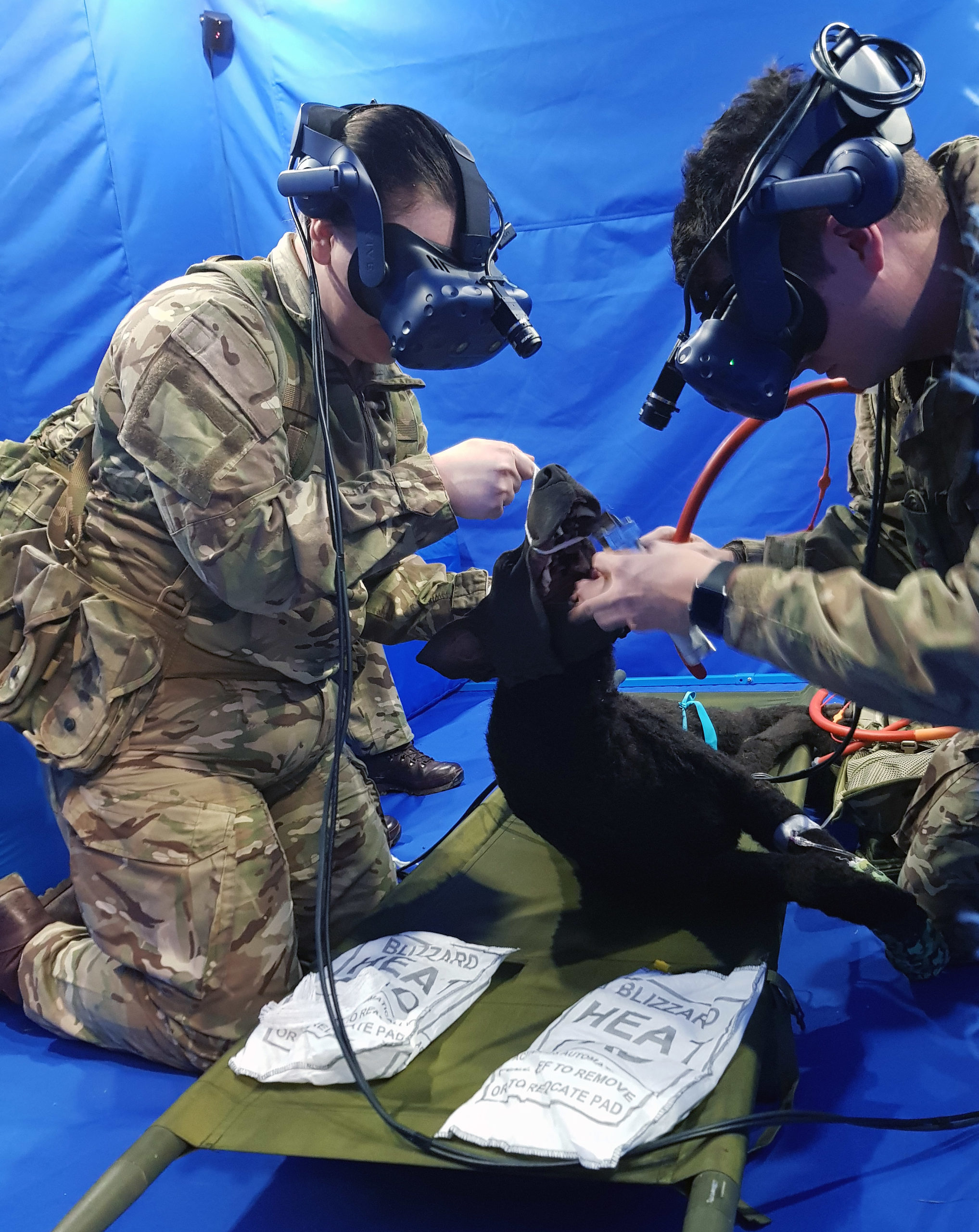

The legacy of VRS and the MISTVR project continues to this day and actually drives our belief in the power of “Mixed Reality” – integrating real-world physical objects within virtual contexts. Later projects continued to prove the value of this approach, especially given the expense and questionable reliability of many of the human interface products appearing on the market. Projects such as a close-range gunnery trainer for the Royal Navy, where we used actual inert weapons to recreate the bodily loads and torques facing gunners when slewing the weapons. Projects such as our helicopter “voice marshalling” VR trainer, where we provided a physical mock-up of the rear-door working space for trainees who were learning to give accurate verbal approach and landing guidance to pilots. And, more recently, our Medical Emergency Response Team (MERT) trainer, where we use realistic physical “casualty” mannequins and, where deemed essential to training, items of medical equipment. These are viewed using camera-modified “pass-through” VR headsets and, using blue-screen chroma key techniques trainees can visualise and interact naturally with those physical elements within the virtual context of a Chinook helicopter.

I joined academia in 2003 and, in many respects, landed on my feet, in that both the University of Birmingham and I had, separately, become members of a successful consortium bid to establish one of the Ministry of Defence’s Defence Technology Centres, in our case focusing on Human Factors Integration (HFI DTC). After 9 years, we were able to build on the experience gained during the earlier VRS projects and had amassed yet another huge portfolio of defence “concept capability demonstrators”, all underpinned with sound human factors principles. We were involved in the development of so many unique VR training and visualisation projects, from SubSafe, a project where we had to build the forward end of a nuclear submarine from scratch and carry out weeks of experimental evaluations at Devonport, to a remote driving and manipulation training simulator for the CUTLASS bomb disposal system, another example of Mixed Reality demanding the construction of a physical replica of the actual control workstation.

And, maintaining the philosophy of early and iterative engagement with end users and subject matter experts, these projects exposed me to a wide range of real-world experiences, notably the opportunity to dive off Scotland’s Isle of Arran in the UK’s (at that time) rescue submersible, take the helm of the nuclear submarine HMS Tireless in the English Channel, fly in a search-and-rescue helicopter along the coast of Cornwall, fire a Dillon Minigun off the side of a Royal Navy Type 42 Destroyer, blow up simulated IEDs using robotic technologies and even spend 3 days in the Johannesburg Morgue!

The 1990s experiences of trying to “sell” the concept of VR into a highly sceptical industrial user base – commercial and military – have also served me well, I believe, and continue to do so, even today. But the damage caused in those fragile years of the 1990s and 2000s by the hype and broken, undelivered promises of many “fly-by-night” organisations – both commercial and academic – effectively stifled the technological evolution of VR for many years. In truth, we should be much further forward today than is actually the case. It is unfortunate then that, even in 2022, the lessons learned, particularly in the 1990s, seem to have been completely forgotten and history seems to be repeating itself all over again. Yes, the technologies are much improved and more affordable than back then, but, when it comes to making realistic, credible claims and predictions, things have changed very little indeed.

With all the ups and downs of the past 35 years, I look back on my involvement with considerable pride and with fond memories of an age of significant technical achievement, courtesy of a handful of pioneers on both sides of the Atlantic. My team and I are still very much active in the XR field, choosing to spend most of our time “on the road”, as opposed to what I call the “Academic Centre of Excellence” mentality (which has failed the UK on numerous occasion). Taking VR to real people, doing real jobs in the real world is important to us, as is our ongoing work in public engagement and STEM/Outreach activities with schoolchildren of all ages and abilities. From drone and underwater wreck surveys on Dartmoor and in Plymouth Sound, to 3D scanning of railway carriages, caves and historical sites and artefacts, the reality of Virtual Reality really is delivering content and solutions that both educate and engage. Long may that continue!

About Professor Bob Stone, C.Psychol., FCIEHF

Professor Bob Stone is a Human Factors specialist and the UK’s foremost immersive technologies specialist – a 35-year “veteran” of the international Virtual, Augmented and Mixed Reality community. In 1993, whilst researching VR and robotics at the UK’s National Advanced Robotics Centre, Bob established the world’s first industrial VR team, launching a countrywide collaborative VR initiative, wholly funded by industry.

Bob’s research has taken him from Royal Navy vessels conducting close-range weapons and missile trials to underwater operations onboard submarines and rescue submersibles; and from search-and-rescue helicopter missions to operating theatres and medical units throughout the UK, US and South Africa.

Today, as well as being an Emeritus Professor at the University of Birmingham, Bob works closely with the Royal Centre for Defence Medicine and various UK hospitals, researching the use of VR and MR for physical and mental health restoration and rehabilitation, and for the training of future military Medical Emergency Response Teams. He also has a passion for the Virtual Heritage arena, exploiting VR and AR to help make invisible rural and oceanic historic sites visible once again, particularly around the Plymouth area where he was born and bred.

In 2011, Bob was awarded the Ministry of Defence Chief Scientific Advisor’s Commendation for his contributions to Defence Science & Technology, and, more recently, his team received the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics & Human Factors 2020 Innovation Award for their defence medical work.