One of the surprises of the party conference season has been the focus on the concept of ’15 minute neighbourhoods’ – and not for the reasons that you might expect.

In this article, Tim Fawcett (Birmingham Cities Lead, Mott MacDonald and Chair of CNM Infrastructure Board) explores the origins of the concept and what the notion of ’15 minute neighbourhoods’ could do to transform communities across the West Midlands and beyond.

(October 2023)

What makes some places really desirable, and others less so? For some people, living somewhere tranquil and having easy access to nature trumps all. For other people, living near to their family is more important than anything else. Where people live really matters; it’s one of the most personal choices you’ll ever make.

For many people in towns and cities, convenience is also really important. Neighbourhoods with good access to services and amenities we use every day like schools, doctors, shops, cafes, parks, and railway stations are more attractive, and often have higher house prices. One way of describing a place like that is a ’15-minute neighbourhood’.

15-minute neighbourhoods have gained significant traction as an idea in urban planning over the past few years. Carlos Moreno, a Colombian-French urbanist, author and academic coined the phrase ‘Ville du quart d’heure’ (15-minute city), and the idea has taken on a life of its own, with Anne Hidalgo making it a central plank of her successful pitch to become mayor of Paris in 2021.

The idea is simple enough. A 15-minute neighbourhood allows people to access most of their daily needs within a 15-minute walk or cycle from their homes. The idea is to promote local self-sufficiency, reduce the need for car travel, and create more sustainable and cohesive communities. However, they have also increasingly been attracting controversy. That controversy has largely been from conspiracy theorists or people with genuine concerns based on a misunderstanding of the idea. However, in recent weeks senior UK politicians have also joined the debate, with the Transport Secretary saying “what is different, what is sinister and what we shouldn’t tolerate is the idea that local councils can decide how often you go to the shops, and that they ration who uses the road and when, and they police it all with CCTV”. These words reflect some of the more fanciful conspiracy theories, and are not what urban planners, policy makers and designers are trying to achieve.

What are the benefits of 15-minute neighbourhoods?

If you can choose to walk or cycle to the shops, school or playground safely and conveniently may people will. This has direct benefits to the individual, but also to wider society. If you take fewer trips by car and more by walking or wheeling you’ll be healthier, get to know your neighbours, and save money. Fewer car trips also means fewer accidents, better air quality, reduced carbon emissions, lower noise levels, better health outcomes. Congestion also decreases, so more space is made for people who do choose to drive, public transport and emergency services. More people using local shops and services helps small businesses thrive, and can lead to better social cohesion as social interactions increase, in turn leading to more inclusive and resilient communities. There are multiple and interlinked social, economic, and environmental benefits for everyone.

They are not a way to take away freedoms, to remove the choice to drive, or to control people as has been suggested.

How can we measure 15-minute neighbourhoods?

The idea is simple really, but how can we define what a 15-minute neighbourhood is? At Mott MacDonald we’ve developed a basket of amenities we think most of will be present in a 15-minute neighbourhood. They are shown in the below graphic.

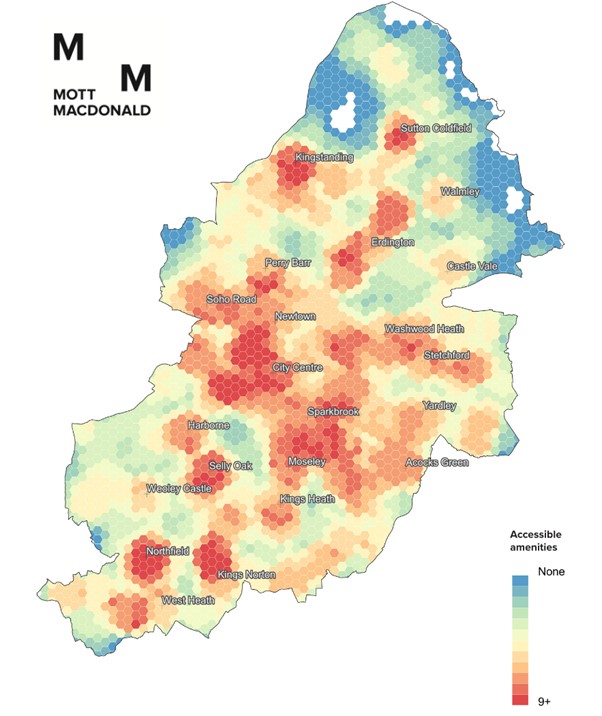

We also developed a methodology to assess accessibility to these services from any given point within a reasonable time by walking or wheeling (i.e. without motorised transport). We applied that to Birmingham, and the resulting heat map is below. Red areas have really good access to the services and amenities we use most frequently. Areas with cooler colours have less good access.

A really clear pattern emerges. As you might expect, the city centre and other inner-city areas have really good access to the basket of amenities. So too do many recognised thriving neighbourhoods – Selly Oak, Kings Norton, Sparkbrook, Perry Barr, Sutton Coldfield. The thing that unites those places is that they were planned or developed before mass ownership of cars. Before cars, neighbourhoods were laid out to meet the needs of people walking and cycling so everything you needed had to be within easy reach. Often they would also be served by railways and tramways as well to get access to places further away.

But after car ownership started becoming more common (more households had access to a car than not from the 1960s), cities started to be planned for the car as a ‘first choice’. You didn’t need to have good access to everyday amenities within walking and cycling distance of every house – you could just drive. That has led to ‘amenity deserts’ – whole areas of the city which have poor access to the things we need for daily life unless you drive. It has also led car-dominated cities meaning congestion, poor air quality, carbon emissions, decreased physical activity, reduced child independence, and other side effects of car dominance.

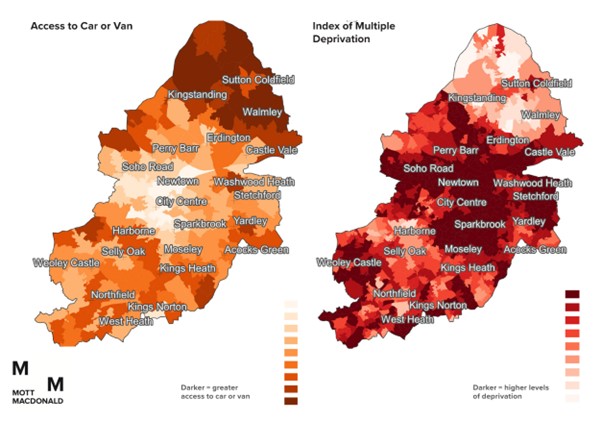

The socio-economic impact of amenity deserts

When you map out households with access to a car or van, unsurprisingly there’s a partial correlation to the level of accessibility to the basket of amenities – but it’s not an exact match. Some people who live in areas where it’s easy to access things without a car still choose to have a car, for example. When you map out the indices of multiple deprivation (which measures things like income, employment, level of education, and health) there is a clear correlation between deprivation and car ownership – areas with higher levels of deprivation have lower levels of car ownership. But comparing the three maps leads to some interesting observations.

There are some areas where there is low deprivation, good access to amenities, and high car ownership. People who live here could be categorised as having good access and having a choice. These are places like central Sutton Coldfield, Harborne, and Kings Norton.

At the other extreme of the intersection between these measures, there are some areas with high deprivation, poor access to amenities (amenity deserts), and low car ownership. The choices of people living here are much more restricted, and it inevitably affects their opportunities to access education, training, employment, and the services we all need to live our lives. If you don’t have access to a car (for example you’re too young, can’t afford one, or have a disability that prohibits driving), and live in an amenity desert, what do you do? You need to spend a lot of time getting to amenities that people with cars, or live in 15-minute neighbourhoods can take for granted. Because of the urban grain (the layout of streets and development blocks) in amenity deserts was planned for driving as a default (e.g. lots of poorly connected cul-de-sacs), often access to public transport can be poor, and the services can be slow and infrequent.

Convenient access to amenities can be looked at through a social justice or equity lens. How do we make sure the most vulnerable in society aren’t further disadvantaged because of where they live?

How do we achieve 15-minute neighbourhoods?

Building on what we’ve got: Some neighbourhoods already have good access to amenities, so the focus in these areas should be to make it safer and more convenient for people to walk and wheel. One of the key ways to achieve this is to make it less convenient to drive. This can be controversial and does lead to strong, emotional reactions from people, but without achieving the latter, it’s not really possible to achieve the former. Crucially cars will still be able to access every street, but not as directly and conveniently as people walking and wheeling. This is core to urban planning in many places in continental Europe – Groningen in the Netherlands and Ghent in Belgium are often held up as architypes. If you visit those places it’s really clear that the quality of life is high and people enjoy the real freedom 15-minute neighbourhoods bring as opposed to the lack of choice and car-dominated public realm of many UK cities. What is absolutely clear is that to be successful and accepted these changes must not be imposed on communities, but developed with residents through collaboration and inclusion.

Planning new places: In some places we have the luxury of planning new parts of the city from scratch. In Solihull, around the HS2 Interchange Station, Mott MacDonald is working with the landowners and developers to design Arden Cross, a 140 hectare (346 acre) mixed use development (find out more here). The masterplan has been designed using 15-minute neighbourhood principles to encourage walking, cycling and sustainable movement patterns. It links new public parks and civic spaces, and enhanced natural landscape features in a network of activity corridors, providing public amenity as well as an ecologically-rich wildlife habitat. This strategy is reinforced through distinct development of character neighbourhoods, focussed around living, working, play, and leisure – making sure that everyone that lives and works there will have access to many of the amenities they will use every day without needing to get in a car.

More radical change: Some neighbourhoods which are currently amenity deserts will be harder to reimagine. How can we introduce easy access to amenities in places which are typically low density with poor pubic transport connectivity? There’s no easy answer. In the longer term, we need to change the urban pattern, densifying where appropriate to make sure businesses and services which provide those essential amenities are economically viable. In the shorter term we need to make sure public transport is as good as it can be. That may mean thinking differently about how people access public transport, and in lower density areas moving away from fixed-route, fixed-timetable public transport routes, and introducing demand-responsive transit as being trialled in Coventry and Warwickshire (think public transport minibuses accessed via an Uber-like app).

Transport for West Midlands have recognised the importance of 15-minute neighbourhoods within their strategy document ‘Reimagining transport in the West Midlands’ (read it here), and local authorities across the region are planning interventions to achieve related policy objectives. Regardless of political headlines, good urban design and city planning will continue to decarbonise our communities and make places better for all people to live healthier and happier lives.

ABOUT OUR AUTHOR:

Tim Fawcett is Mott MacDonald’s Birmingham Cities Lead, bringing together the best of Mott MacDonald to solve challenges and maximise opportunities in the West Midlands. He leads sustainable cities, urban development and transport projects for clients across the region.

He is chair of both the Infrastructure Leadership Board at Centre for the New Midlands and the Civil Engineering Industry Advisory Board at Coventry University.

Carbon gets mentioned 3 times in this article. I think we know what the agenda is. Meanwhile India rejoices at mining 1 billion tonnes of coal for the first time last year.

Hi Tim,

Great article but I think your controversial statement making it less convenient to drive needs the addition of making it easier and more convenient to walk and wheel.